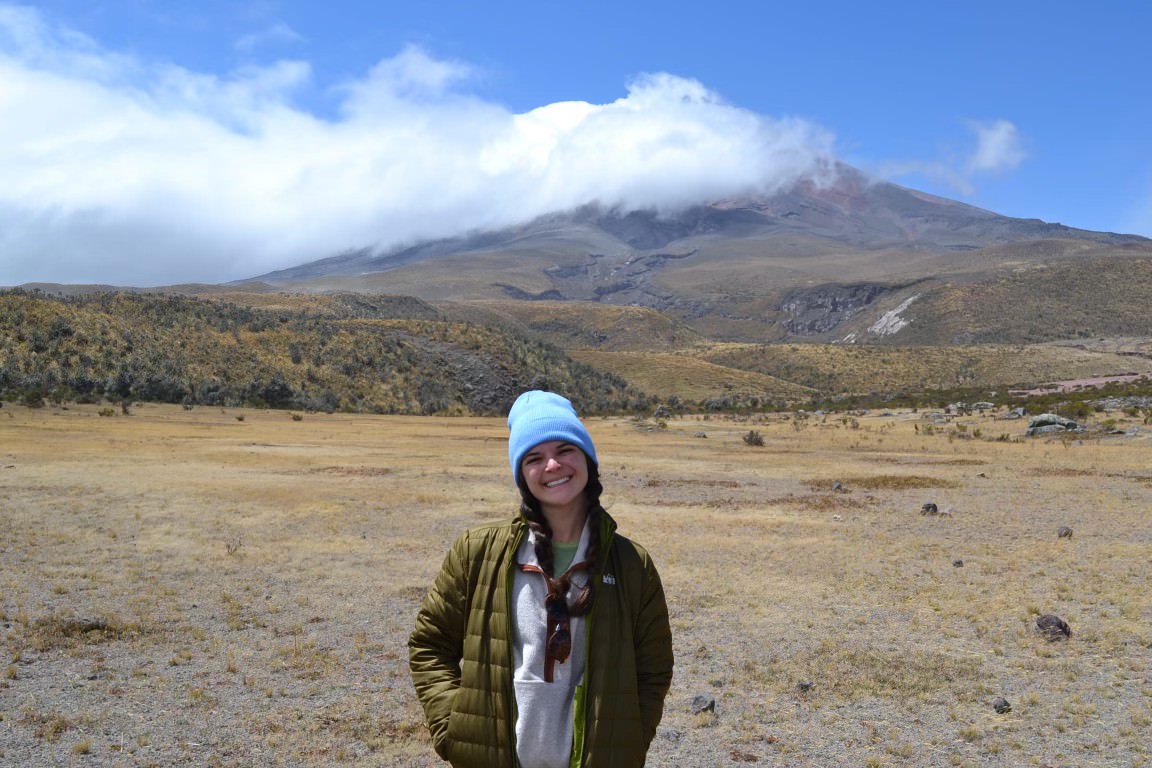

Kendall Weaver reflects on her experiences in the Middle East

“You want to tell people about your experience, but you also don’t want to feed into stereotypes,” reflected Kendall Weaver, ’20, while discussing her time studying abroad. As the Presidential International Scholar, Weaver spent her fall semester studying humanitarian aid in Amman, Jordan, followed by research conducted in Palestine and time living in Jerusalem.

For Weaver, her semester in Jordan was an adjustment to living in Jordanian and Middle Eastern culture. Part of the culture shock she experienced came from simply living in a place where the public spaces were filled with men. “Jordanian women don’t go to the grocery store–they get their son or their husband to do it…they don’t leave the house. And there’s a lot of reasons for that and a lot of it varies on family.” One family with which she interacted was conservative, so every time they went out, “they had to put on gloves; they had to wear full covering.” Because of this, she explained, “they just didn’t go out unless it was a special occasion, because it’s just a lot of effort.”

In spite of this cultural reality, Weaver lived with an older woman, who has been single since she was 23 and spent her younger years as one of the first feminist activists in Jordan. Weaver described a conversation she had with her host mom, who said, “American women think that we’re oppressed as women in Jordan, but really, it’s just that Muslim men pamper their women and they don’t make us work and they let us just lounge around the house in our pajamas all day.” Despite assertions such as this, Weaver also met young women who felt the pressure of marriage. She described friends who knew that, despite their education and skill sets, their parents would force them to marry if they did not do so in the next few years.

In both Jordan and Israel, Weaver experienced her fair share of cat-calling. Part of the cultural structure in which men fill most public spaces lends itself to this; however, Weaver figured out a way to cope with it. During one instance in Jerusalem, some men started whistling and calling to her, to which she responded in Arabic “I know! Thank you very much.” Her language skills helped her in dealing with situations like this, but either way, she recognized that she needed to adapt. “I just kind of learned to take it in stride. I can either let this make me scared or I can act like I don’t care.”

Gender was not the only divide Weaver saw her during time abroad, though it was ingrained in the Jordanian culture. While traveling into Israel, Weaver described a particular incident: “I traveled with my friend, who is Muslim and he’s black. He’s actually Ethiopian originally, he’s a first generation American and his parents were…refugees actually. And so he very much looks the part and then his name is very Arab and they took one look at his passport…and they were like ‘we need to do an extra check on your bags and anyone that’s with you.’” She saw this as an example of the minority being excluded by the majority, which is a problem in the Israeli/Palestinian area.

In general, the issue there is complicated because, as Weaver described, “it’s this beautiful, European-esque society smack next to poverty. And then I reminded myself that there are parts of the U.S. that really look like that as well.”

While in Palestine, she interned with UNRWA, interviewing refugees on a daily basis and traveling to camps.

Weaver prepared for her research by studying the structure of aid through her SIT program in Jordan: “We talked a lot about the UN cluster system and how these big governmental organizations funded by the UN trickle down to international organizations who are then in charge of local CBOs.” The program gave her an understanding of the structure of humanitarian aid, but not necessarily enough to prepare her for the shock of spending time in refugee camps, interviewing refugees.

In order to emotionally deal with the events around her and people assuming her experiences were difficult for her, Weaver reminded herself of her privileged position. “I just had the perspective of ‘I get to get on the bus and I get to come back here…eventually, I get to go home to America where I have every opportunity and I will most likely never see my sibling killed in the street’…seeing that is not hard, living that is hard. I can handle seeing it.”

Weaver wrapped up her time abroad conducting research and developing her language skills, hoping to eventually return to the region and continue to serve the refugees through humanitarian aid programs. She recognized that encounters like these can be difficult but also knew the value of the time spent studying and researching. “I had to make the most of my experience because literally nobody was going to do it for me.”