What it means to be on sabbatical

For most students, few things can be more disappointing than waiting years to take a class with your favorite professor only to find out that they’ll be on sabbatical.

But what is sabbatical? What are professors doing while they’re away?

“Sabbatical” comes from the same root word as “sabbath,” and the purpose is largely the same: giving people, in this case professors, the chance to rest, recharge, and return more energized.

Contrary to popular belief, sabbatical is not simply a semester-long or yearlong vacation for professors to lounge around and step away from their studies — in fact, it is quite the opposite. As professors typically dive even deeper into their research and into new developments in their fields that may have arisen while they were teaching full-time.

At Wofford, establishing a more regular sabbatical system for professors became a greater priority when President Samhat arrived on campus — a process that Stacey Hettes, professor of biology at Wofford and then-associate Provost for faculty development, was also instrumental ins.

“When Dr. Samhat came to Wofford as President,” Hettes said, “he saw that there were some challenges for Wofford professors with our emphasis and goals to be the best teachers that we can be to make room for and prioritize our scholarship.”

The goals that professors had to prioritize their scholarship at the time came in the midst of an irregular sabbatical schedule that saw many professors not having what were then more commonly referred to as “development leaves” for 15 or even 20 years. In fact, according to Hettes, some professors never took their leaves at all. However, that changed under Samhat. Now, sabbaticals typically take place every seven years for professors.

“(Dr. Samhat) was really the one who, when I first became associate provost for faculty development, gave us the permission to look at this and think about it and say, can we set up a system and a practice of having these be more frequent for people?” Hettes said.

So how do professors use their sabbaticals now? Well, it varies.

Natalie Spivey, associate professor of biology and lead health careers advisor at Wofford, used her sabbatical to design a totally new course — now Biology 400 — that did not exist before.

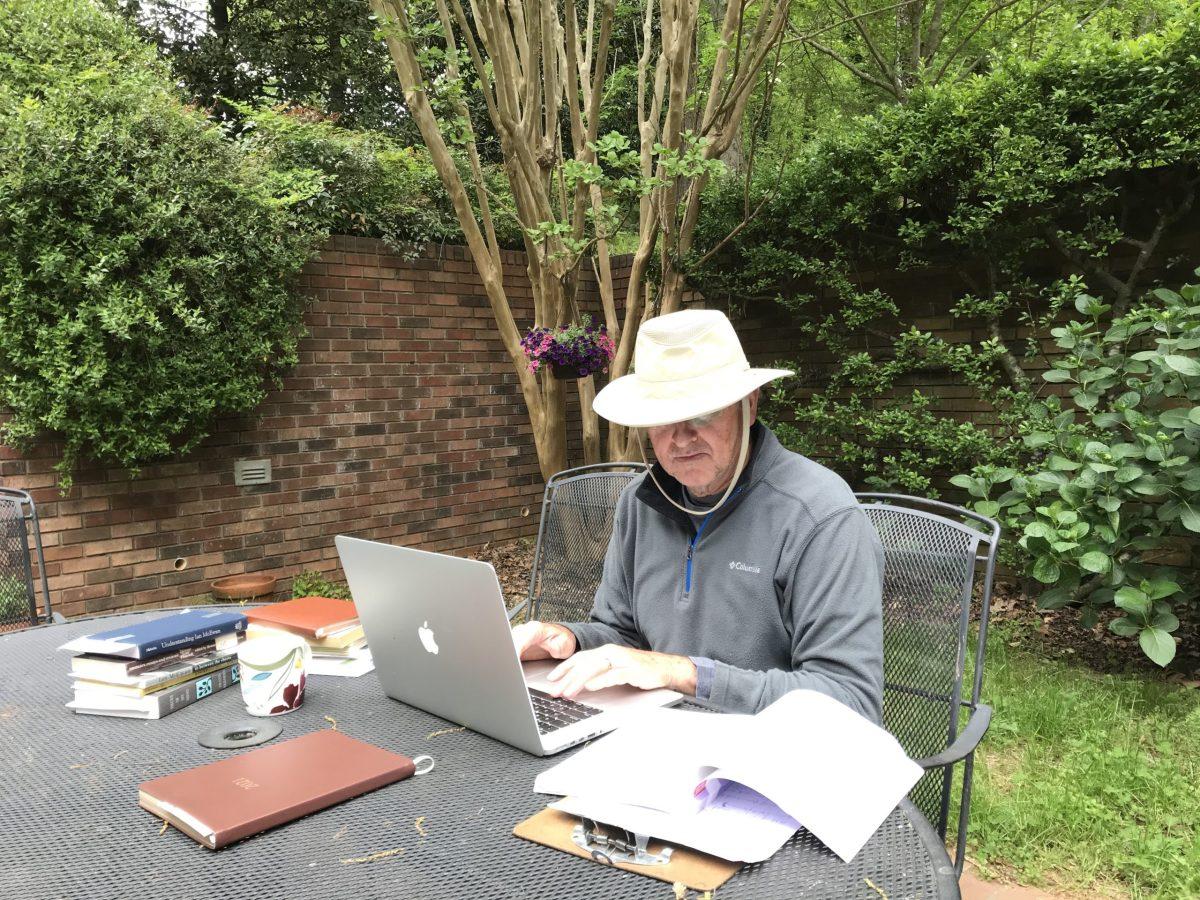

Alan Chalmers, professor of English, has been on sabbatical since the start of the spring 2021 semester and has devoted his time away from Wofford to conduct research within his discipline.

“I developed a daily routine,” Chalmers said. “Most of the time I wrote in the mornings, read and exercised in the afternoons, and edited in the evenings.”

In the midst of his daily routine, Chalmers admitted that one of the toughest parts of sabbatical has been missing out on the regular interactions with students and colleagues that he had grown so accustomed to during his normal semesters on campus. Despite this, he highlighted the importance of having the time granted by sabbatical to strengthen himself as a scholar and strengthen Wofford as an institution.

“Sharing our research is one way the college speaks to the world,” he said. “Without the formal support of the college in the form of sabbaticals, this sort of work becomes very difficult or impossible. As dedicated teachers, during regular semesters we devote our energies primarily to our students, and to the daily demands of college life.”

Other professors within the department, such as Kimberly Hall, assistant professor of English, plan to continue projects that had been slightly slowed by the rigor of the academic year. Hall intends to finish a monograph that has been in progress for the past few years, and she will be on sabbatical for a full academic year to do so and to explore and complete other projects within her field including presentations and articles.

“Returning to that focus just allows you to develop a depth to your work that sometimes you can’t if you’re spread in different directions, not just teaching but really the kind of service component of a professor’s job can be really time consuming as well,” Hall said. “So, stepping away from some of those responsibilities will allow me not only the time but just the mental capacity to focus more on my research.”

Hall added that she, like Chalmers, expects the most challenging part of sabbatical to be the time spent away from students, but she also sees the value in being able to step away and recharge before returning to her regular work as a professor. She cited her colleague Julie Sexeny, associate professor of English, as an example of a professor who she has seen return from sabbatical with great energy and passion.

“Dr. Sexeny came back and just has been—she was amazing before, but it really seemed like recharged and energized and picked right back up where she left off,” Hall said. “And most of my colleagues, I think, come back feeling energized and ready to get started again so I haven’t noticed (a drop-off) in someone else but I am nervous about it a bit for myself.”

As Wofford continues to move through the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic and the restrictions that have come about, sabbatical during such a unique time may end up being more rewarding than it is costly.