By Katie Kirk & Aiden Lockhart

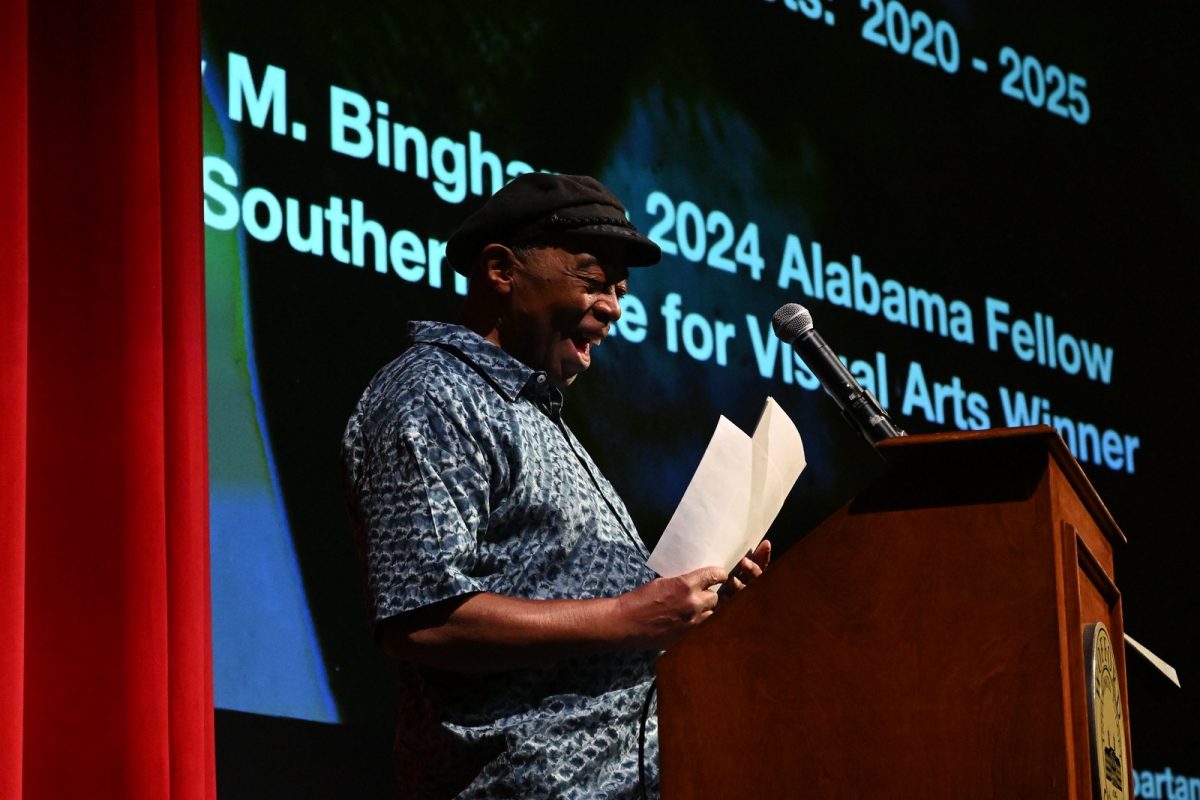

Hispanic Heritage Month began Sept. 15 and lasts until Oct. 15. The office of Inclusive Engagement ar- ranged for Saul Flores, a philanthro- pist, photojournalist and speaker, to visit Wofford on Sept. 20. He spoke about his journey dealing with his Latin American heritage and com- munity engagement.

Seth Flanagan ‘18, assistant direc- tor of inclusive engagement, high- lighted the need to have an event like this, as the Wofford community has a tendency to exist in a bubble.

“We are in the business of creating global citizens that can affect change wherever their path in life may take them,” Flanagan said. “It is essen- tial that while students are here, we provide opportunities for students to experience the world outside of Wofford.”

The talk, held in Leonard Auditorium, started with the story of Flores’ childhood in New York City with immigrant parents. Throughout his childhood, Flores became more aware of how hard his parents were working. He wanted to make the most of his opportunities, and this proved to be a theme throughout his story.

Isaiah Franco ‘23, international affairs and Spanish double major, serves as the Vice President of the Organization of Latin American Students. Franco is a member of the Latinx community on campus who attended the talk.

“My experience as a third-generation Puerto Rican overall is so different, but hearing about his parent’s sacrifices reminded me of my child- hood,” Franco said.

When Flores applied to colleges, he received a grant that gave him the opportunity to make a difference in a community that he belonged to. His first thought was to arrange a trip back to his mother’s hometown, in Atencingo, Mexico, with other college students.

While visiting his mother’s home- town, they had the opportunity to see what the elementary school his mom attended was like.

Flores discovered that the children in the elementary school were ready and eager to learn. However, he also found the building to be in disrepair. Later that same day, the principal told Flores that the school was in danger of being shut down.

This trip to Atencingo sparked a deeper question for Flores. He wondered what he could do going for- ward to improve the opportunity for education for these children. Flores decided to do something extraordinary: to recreate an immigrant’s journey starting from Quito, Ecuador all the way to Charlotte, North Carolina.

“I learned that Ecuador was a starting point for a lot of migrants,” Flores said.

Along his journey, Flores commit- ted to taking pictures. These photo- graphs would be sold to repair the school in Atencingo, Mexico. These repairs and renovations would en- sure that the lower-income students would have the ability to get an ed- ucation if the school would remain open.

His journey was strenuous and dangerous. Flores mentioned one instance where he was close to death in the Darién gap in Colombia. In this area, Flores unknowingly came into contact with the venom of a

poisonous dart frog, causing him to go unconscious for a few days. He spoke about his fear from being so close to death.

Flores mentioned that the Mex- ico-United States border was also taxing to cross. This was not only due to the extreme danger but also the heaviness of knowing that this was the place that most immigrants had to cross to get to the United States.

“The trickiest part to cross next to the Darién Gap was the Mexi- can-American border. I was trav- eling through Juárez, which was one of the most violent cities in the whole world,” Flores said. “I think that in the few days I was there, 46 people were murdered.”

Upon the completion of his jour- ney, Flores sold the photographs he took along the way. He was able to raise enough money to keep the school in Atencingo open.

Flores also gave students a chance to share stories with one another during his talk. He asked those in attendance to close their eyes and think of a moment in their lives when they realized that someone was making a sacrifice for them.

Afterwards, he gave students the opportunity to share. Flores believes that giving students a chance to re- flect can be a powerful part of inspir- ing change.

“I wanted to give students an op- portunity for students to look in- wards and backwards and to look through where they are coming from, giving them a stronger direc- tion to start projects like this,” Flores said.

Flores’ story can be a source of in- spiration for students who want to make a difference in the local Spar- tanburg community and on campus. Flores was able to use his passions to motivate him to make an impact on his community.

“I hope students take away the no- tion that hard work does pay off,” Flanagan said. “As a student, you can effect more change than you can imagine, both on campus and off.”

Several students see struggles in being part of a small Latinx commu- nity at a predominantly white insti- tution.

“I think being Latine at Wofford is just so hard because there are so few of us,” Franco said. “In conjunction with this, it is hard to plan events or ensure the longevity of OLAS because almost everyone has to be involved to feel like things get done.”

For non-Latinx members of the Wofford community, according to Franco and Flores, learning about culture is drastically important to personal growth. Students should immerse themselves in different Lat- inx contexts and educate themselves about those cultures.

“There are millions of immigrants in our country, and thousands that make the journey each year. In Spartanburg, there are dozens of migrant groups who have made a home here. (Flores) was able to tell some of their stories through his own voice,” Flanagan said.