By: Laura Barbas Rhoden, Contributing Writer

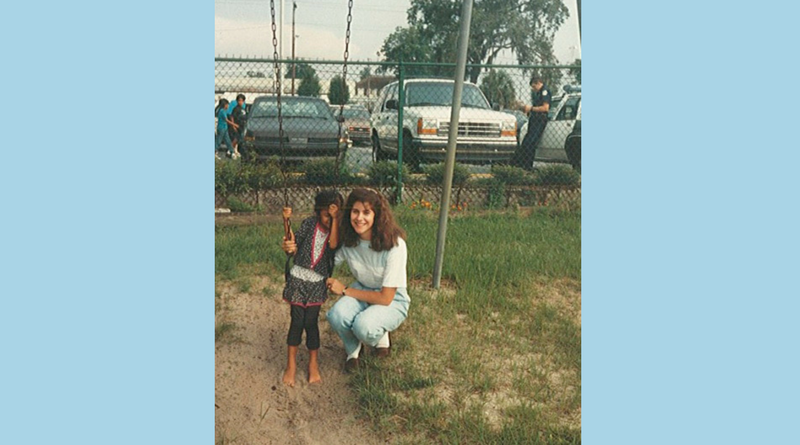

For over two decades, I’ve had the privilege of being an educator of some of the most hard-working, talented, young people you’ll ever meet. Truth be told, though, I’ve been teaching even longer. Some of my first students were little kids whose parents took English as a Second Language classes on Sunday nights at First Baptist in Valdosta, Ga., where I volunteered in high school. In those church education wings and in the rural schools nearby, I first encountered the immigrant community whose lives would be entwined with my own, and the lives of my students, for decades to come.

In the immigrant community are DREAMers, young people brought to the United States as children, some as infants, by families who wanted them to grow up in a place without violence, with the possibility of education, where hard work could be rewarded with a decent life. And those parents found work in communities like Valdosta and Spartanburg. They helped build roads and office parks, cleaned hotel rooms, landscaped yards and washed dishes. Their kids grew up with other kids in the United States, playing soccer and taking field trips, singing the fight song at the football game and saying the Pledge of Allegiance at the start of the school day. As I studied and worked in communities in the new American South, half a generation ahead of them in age, I saw their lives unfold: they were like those around them and yet unlike those around them.

DREAMers aren’t American citizens or legal residents of the country they call home. For many kids, dreams collided with the reality of being “out of status” as they grew up: no work permits; no financial aid; no path to legalization, which is a sophisticated way of saying they had “no line to get into” to become legalized. DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals) was a temporary fix, the act of a president pressured to do something, anything, because Congress wouldn’t pass immigration reform to deal with a challenge business owners, pastors, teachers, and law enforcement officials had been asking it to deal with for years.

Congress has a chance to pass reform now in the shape of immigration reform for DREAMers, to offer young people like the ones I’ve met in our Upstate community an opportunity to get right with the country they call home, and a chance for this country to get right with them. Many DREAMers have used their DACA status to serve in our military, earn their degrees, help businesses prosper, and make our communities safer and stronger. How do I know? I’ve seen them face-to-face, heard their stories and talked to their employers. “I’ve known our government to do some stupid things,” one business leader said at a meeting I attended, “but not fixing this is at the top of the list.”

The United States needs sensible, pragmatic and humane immigration reform to ensure our shared prosperity and affirm our values. Failing to reach a legislative solution for DACA recipients will cost the United States $200 billion dollars in future economic gains, according to a CATO Institute study, plus another $60 billion in direct costs to our government. Other studies put estimates even higher. What does inaction cost our country? What will future generations say about our actions today?

When I look back at those distant days in south Georgia, I see the legacy of people who believed that hard work has value and that work goes better when we tackle it together. It’s time for Congress to learn those lessons, too: to come together to do the work of immigration reform, and let DREAMers keep making America stronger.

Laura Barbas Rhoden is Professor of Spanish at Wofford & founding coordinator of Hispanic Alliance Spartanburg.