By: Lydia Estes, staff writer

When Dr. Thomas Wright, math professor, returned from Antarctica at the end of a sabbatical of traveling and book-writing, his next adventure was to take an interim group to Nepal and Tibet. Dr. Jeremy Henkel and 19 students joined Wright on a religious pilgrimage through the monasteries and temples, which characterize the two nations’ strong religious values.

I was one of the lucky ones to be a part of “To the Roof of the World: Life in the Shadow of Mt. Everest,” a course focused on the religious practices and histories of the region surrounding the world’s highest mountain.

The itinerary began with four days in Kathmandu, Nepal. We explored the alleyways of the neighborhood of Thamel that surrounded our hotel. Our tour guide, a Nepalese man with enough knowledge to carry on a conversation in seven different languages, led us on tours of palaces and important city centers, known as “durbar squares.” Kathmandu, Bhaktapur, and Patan durbar squares are all UNESCO World Heritage Sites. He shared stories of the 2015 earthquake and highlighted the efforts to restore the collection of damaged structures and artifacts.

Although seven students were temporarily (for a day) hospitalized due to food-related bacterial infections, the group then flew from Kathmandu to Lhasa, Tibet. Our tour guide in Tibet, Kondol, greeted us in the traditional manner of wrapping a white silk scarf around our necks. At an elevation of approximately 12,000 feet, Lhasa is home to the historical residence of the Dalai Lama, the Potala Palace.

Tibet, a historically oppressed region of China which has fought for independence since the days of the Cultural Revolution, was once politically and religiously ruled by the Dalai Lama until the 14th Dalai Lama fled to Dharmsala, India where many Tibetan Buddhists sought exile. It was not uncommon for Kondol to explain that some part of any monastery which we visited had been partially or entirely destroyed during the Cultural Revolution. We learned, too, that while China eventually wants Tibet to be a part of One China, those born in Tibet cannot receive passports and therefore cannot travel.

Before I registered for this interim, I was unfamiliar with a person known as the Panchen Lama. He’s closely affiliated with the Dalai Lama but historically resided at the Tashilhunpo Monastery. In an effort to undermine Tibetan independence movements, China allegedly kidnapped the 11th Panchen Lama in the 90s and named another Panchen Lama. While visiting the Tashilhunpo Monastery, Kondol informed us that the 11th Panchen Lama lives in Beijing, while our group generally understood that the Tibetans don’t know where their Panchen Lama currently resides. I turned to Wright to clarify, and he pointed to a security camera inside the main chapel. It was then I realized that Kondol was propagating a lie created by the Chinese, which further suppressed her people’s freedom of speech in order to protect herself from the police.

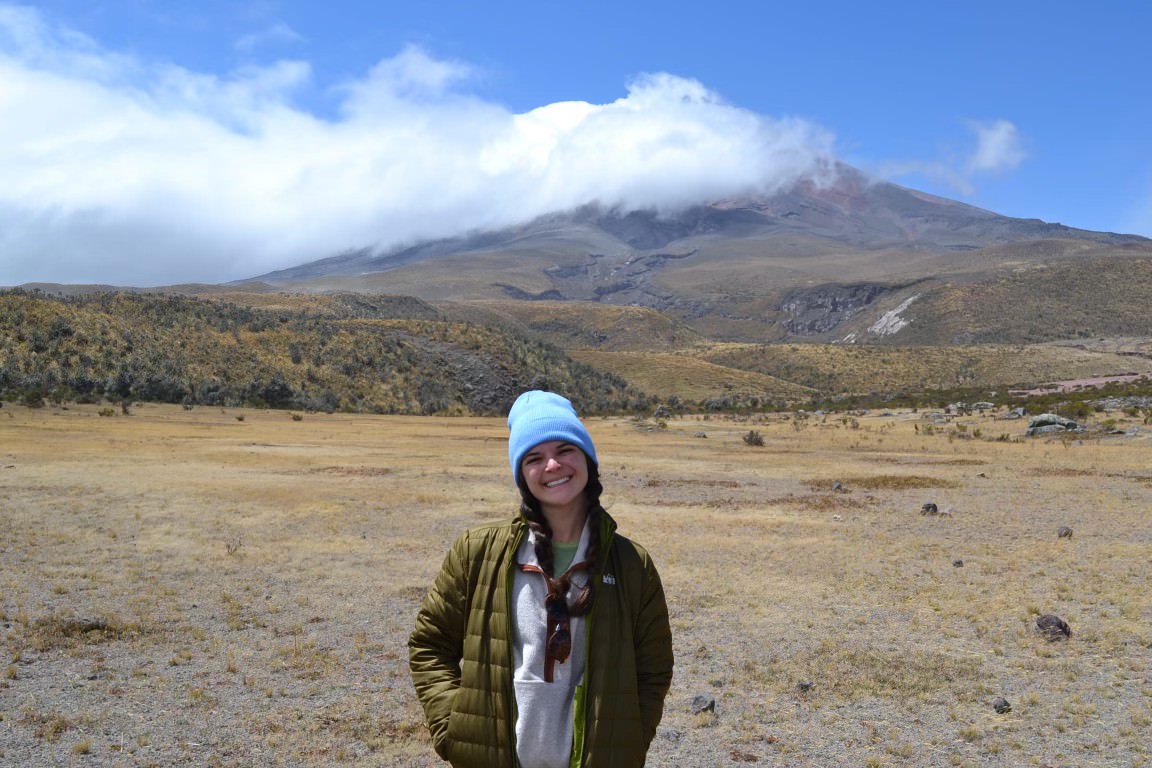

After Lhasa, our road trip through the Himalayan mountains began. We visited small villages like Samye and Gyantse, larger “Chinese-style” cities like Shigatse, and eventually a small town known as Segar which rests a mere 2 hours from Everest Base Camp. Most of us had felt sick or anxious at one point or another, but the air on the morning of our visit to base camp felt hopeful and light—possibly just from the thinness of the atmosphere at nearly 17,000 feet.

We had a chance to tie our white scarves from the first day to the highest mountain pass we would encounter—higher in elevation than base camp—to symbolically ask for good health and fortune for our families. Permitting the Chinese government would accept our alien status, Jan. 19, 2018, would be the day Wofford students and professors stood at Everest Base Camp.

The bus climbed the switchbacks for about two hours, and eventually we reached the world’s highest monastery, Rongbuk Monastery (16,732 feet). Our walk to base camp was not taxing, but at that elevation, we had to remind ourselves that signs of sickness or insufficient oxygen arise hours after the fact. We trekked in the dry riverbed of boulders, as the glaciers won’t begin to melt significantly until the spring.

After a few miles, we reached a monument that indicated we had made it to Everest Base Camp. The camp ground was empty; peak season is April-May, and there is no reason someone should be stationed at base camp in January. Attempts at climbing and summiting Everest during any time but the target window of 7-10 days in May are practically death wishes.

This meant we had the place to ourselves. Wright brought his travel saxophone, a sopranino, and performed a few songs for us. Then Kondol directed us up a steep staircase built into the side of a hill where we ate our lunches (water and consuming carbohydrates—specifically dark chocolate—are the best remedies against altitude sickness). I can honestly say I’ve never, and probably will never, enjoyed a cooler picnic than the one I shared in the company of fellow Terriers at Everest Base Camp.

We reversed our steps back through the Himalayan foothill until we made it back to Lhasa, the capital of Tibet. The next day, our flight over these snow-capped peaks took us once more to the city of Kathmandu. Even though I believe that most of us were enthusiastic to return to this colorful, lively, un-oppressed country, many of us were just as wistful about the adventures we had endured on our road trip through the Himalayas.