The hashtag “#BlackoutTuesday” garnered 28.8 million posts on Instagram. In practice, millions of black squares were posted on Tuesday, June 2 to show support for Black Americans facing police brutality.

Who posted these squares?

I did, for one. Along with peers, former classmates, friends and family. Influencers, celebrities, corporations, art grams and food grams. Nameless, faceless entities juxtaposed with smiling profile pictures. These black squares ate up the feed and swallowed other content, all in the name of solidarity, or if we’re more honest, clout.

Clout, meaning influence, like the influence of a large social media movement, where using a hashtag feels like doing something, or being a part of something.

I don’t want to be skeptical of the groundswell of support for George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery. I want to imagine that the countless other Black Americans who were murdered without cause are implicitly included in every post.

The sheer volume of the posts is directly proportional to my skepticism; where have all of these people come from? And why did they wait until now to speak up?

New York Times Traveling Reporter Tariro Mzezewa said this better in a dialogue published in The Times:

“I think it’s great that people want a visual uniting symbol of solidarity, but I can also see how people who haven’t said a word in the past — or in the past week — feel like they’ll look bad to their followers if they don’t post. So they post, but with no real intention of listening, learning, donating, protesting or helping beyond the post. The post makes them feel like they’ve done their part.”

The impact of social pressure is real, and just 5 years ago, the current was flowing in the opposite direction. I can’t speak on anyone else’s Wofford experience, and to be clear, I’m sitting at a comfortable intersection of being 1) white and 2) middle class. My point of view should be secondary (again, see what Mzezewa has to say here: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/02/style/instagram-blackout.html).

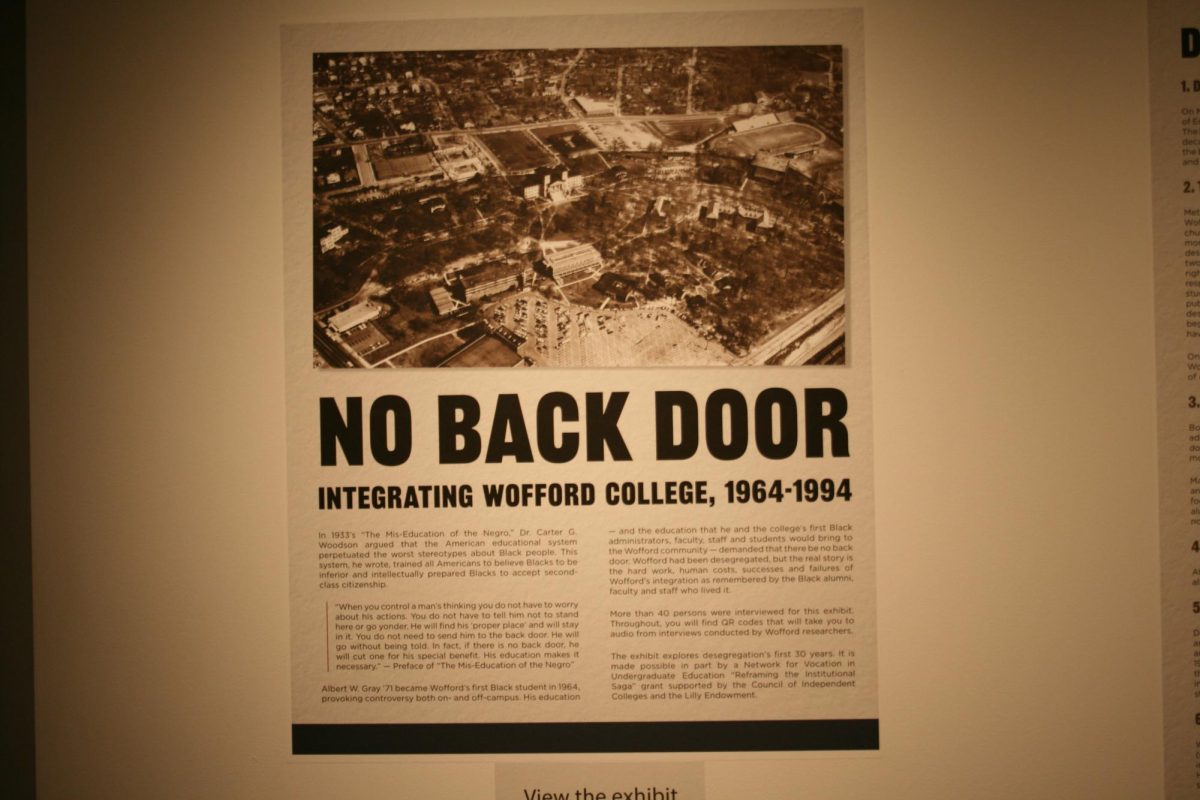

What I do know is this. In the wake of Ferguson, there was no prominent movement on Wofford’s campus.

Instead, there were 20-something students crammed in an Old Main classroom, brainstorming how to maximize a protest while minimizing retribution. It felt like devising a plan to swim in shark-infested waters holding fistfulls of chum. There was no maneuver to get around the sharks; students and faculty alike made it clear how unwelcome a protest would be.

There were also students of color writing articles and op-eds about their experiences on campus for The Old Gold & Black. There were written responses that said “you’re looking for issues where none exist” and “you are the source of the division on campus.”

The sense was that speaking up about racial issues was a burden to others– especially when the dialogue upset the image of the “Wofford Family.” Challenging the status quo meant standing in opposition to decades of tradition and legacies of alumni. It was a vulnerable place to be.

What would it have meant for ten more people to say “we need to be better” five years ago? What would it have meant to have “#BlackoutTuesday” numbers then?

People change. People grow. I don’t want to deny anyone their chance to do better, nor is it my right to make a judgement call. The truth is that numbers are important. It’s literally a life or death situation.

The movement is loud. I hope it stays that way.