A call for commemoration

Jacob Hollifield, managing editor

Regarded as a premier liberal arts school in the South, our alma mater stands unparalleled as an institution of higher education that offers stellar study abroad programs, individualized faculty-student relationships and a classic sense of community—some would say too classic.

Beneath the birkenstocks and stickers on laptops, between the bricks of Old Main and pages of textbooks and behind the doors of Wightman Hall and Greek letters patched over student’s hearts, exists a toxin so strong that it has lasted for centuries, and still plagues the individuals who cross paths with Wofford College.

This past December I presented my research: “The Black, the White, and the Grey: Defining Southern Masculinity Across Race and Time,” before my peers. To start, I detailed the Haitian Revolution led by Toussaint L’Ouverture in the late 18th century, and explained the fear it evoked across the plantations of the South. White southern masculinity, I argued in my research, is rooted in mastery and the ability to conquer, while black southern masculinity is rooted in resistance– the punches thrown at masters, the escapes attempted and achieved, the arms later linked in Selma.

White southern families of the antebellum south, I found, feared their boys would be indoctrinated by the abolitionist ideals of northern higher education. This fear resulted in the endowment of many southern pre-Civil War colleges such as the College of Charleston and the University of South Carolina, as I listed in my presentation. On my third slide, I explained this information, but before I got the “N” in Nat Turner Rebellion out of my mouth, I was constructively interrupted by my professor. “And don’t forget” she said, holding up her hands drawing the attention of the class to where we were sitting, “Wofford.”

How had I, standing on the ground floor of a building erected by slaves, failed to mention the institution whose name was at the top of my research paper: Wofford College?

Recently I have been reminded of the research that I spent weeks conducting and hours compiling. A quote by L’Ouverture comes to mind, “I took up arms for the freedom of my color. It is our own– we will defend it or perish.” And upon a lost battle, “They have in me struck down but the trunk of the tree; the roots are many and deep– they will shoot up again.” In the end, after over 1,000 sugar plantations were burned and a war was fought, Saint-Domingue was the first free colonial society in history to reject race as a method of social ranking. The year was 1804.

It is summer. Wofford’s over 2,000 students are scattered across the country and the world. But, fall is coming. I have been contemplating the possibilities for change that we have been presented with in the United States in the past 5 months and hope that our campus will reflect this experience.

With flames engulfing both the physical and the executive across the country, I cannot help but wonder what ideologies may be challenged or reduced to ashes at 429 N. Church St. when 2,000 plus students with 2,000 plus beliefs look each other in the eyes come August. We have confronted, digitally, the large scale daily racial injustices that unfold nationwide. Soon we will confront, physically, the racial injustices that unfold inside, and are fostered by, the acclaimed Wofford bubble.

Since its founding, the college has valued the monetary over the moral; as a history major and frequenter of the archives I know this to be true. For too many, the question posed is, “What can you do for Wofford?” not, “What can Wofford do for you?” This perpetual message will continue to echo from the city’s Northern border as the Wofford bell has echoed through the Civil War, Civil Rights Movement, integration of the college, and every slur hissed since, until the college fully acknowledges its past and responsibility to educate its students on it.

Can the college condemn racism while tolerating racist people and organizations rooted in racial exclusivity? On the ground floor of the main building, is the engraved sheet of plexiglass shielding over the bricks molded and laid by slaves or shielding us from the shame of our institution? Does a plaque by Gibbs Stadium provide justice to those persons of color pushed away so that white Wofford could expand its campus? The answer: As long as the portraits and 8ft statues of white benefactors of the college shadow over the past, present and future persons of color that bear Wofford in their story, whether enslaved, rejected, harassed, educated, tokenized or employed, no.

Nothing, no matter the thickness of the plexiglass or the thoughts inscribed upon it, can expunge the college from its dark history while its present continues to reflect it. Until we shatter the establishments on campus, at both individual or group levels, and recognize our past, the racially charged history of Wofford College, will tragically be mirrored despite the claim that it is moving forward.

Wofford’s duty to preserve and honor its first Black

On March 5, 1960 on the lawn of the historically Black, Allen University in Columbia, SC, white youth set a cross on fire and hurled bricks at a school building. Albert Gray neared the end of 8th grade at Carver High in Spartanburg, SC.

In the Spring of 1963, following Clemson, the University of South Carolina announced plans to integrate in the coming fall. Following the announcement, over 1,000 USC students marched to the State House on May 3, chanting “we don’t want to integrate.” A cross was erected and set ablaze in the University’s horseshoe. Albert Gray completed his junior year and prepared for his last year of high school.

In September, the university’s first 3 Black students, Henrie Monteith of Columbia, Robert Anderson of Greenville, and James Solomon of Sumter, enrolled. A bomb was set off at Monteith’s aunt’s home, the students were told not to attend football games and were constantly harassed on the way to class.

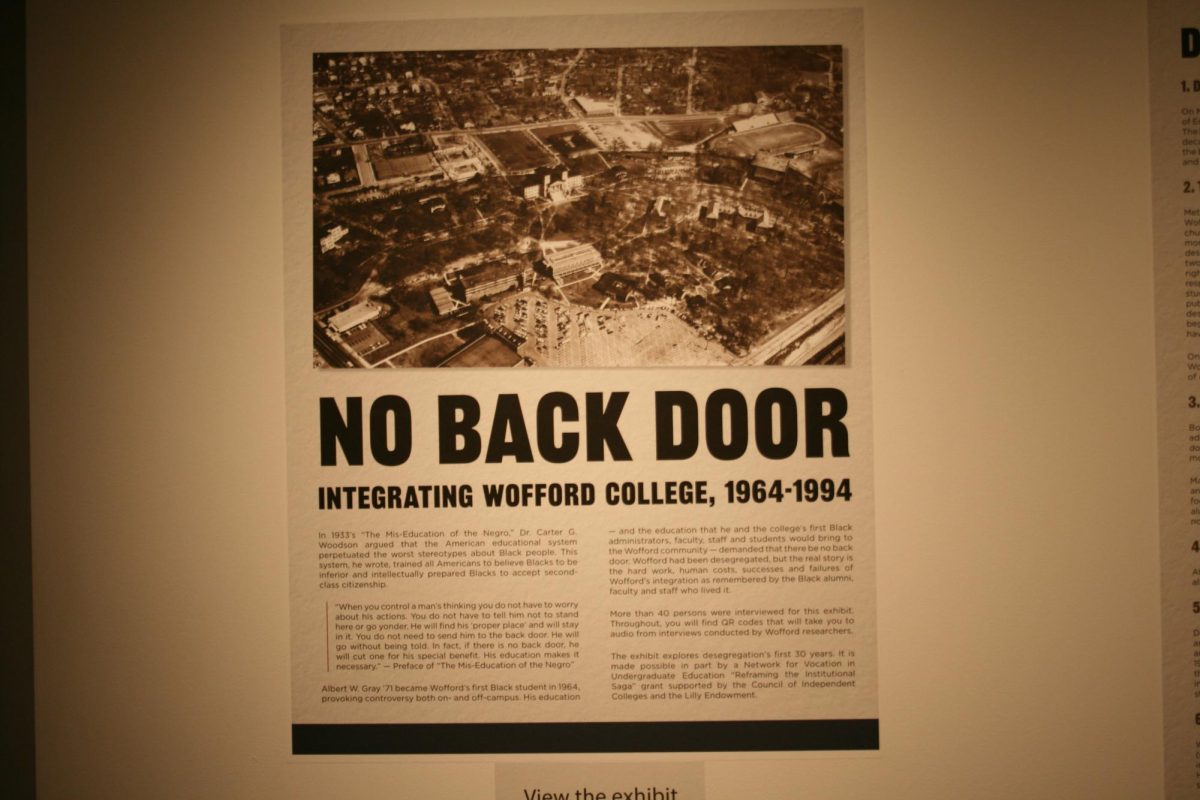

On May 12, 1964, after a Spring full of debate and contemplation among the Wofford Board of Trustees, they endorsed the statement: “[the] admissions policy is applicable to all students who may apply, regardless of race or creed.” Upon the announced plans to integrate the college, Wofford received support from some constituents while others pulled donations and funding from the institution altogether. President Marsh received mail, both fan- and hate-, through the summer leading up to the admittance of the first Black student.

A handful of Black high school students from the Spartanburg area expressed interest in applying to Wofford, but by the application deadline only one had submitted his materials: Albert Gray of Carver High School.

The admissions committee found Gray eligible and on September 8, 1964 he became Wofford’s first Black student. Gray’s Wofford career was put on hold by his service in Vietnam and he resumed his education after the war, graduating in 1971.

Following in the footsteps of Gray, Douglas Jones enrolled at the college the following fall, becoming Wofford’s first Black graduate in 1969.

During their enrollment between 1964 and 1971, South Carolina was a hotbed of racial activity, civil rights advancements and resistance. Sit-ins were staged and broken up by police force, Freedom Riders were attacked in a Rock Hill bus station, Sterling High School was burned down in Greenville by opposers of integration, and, most notably, the Orangeburg Massacre gained national attention in 1968 when highway patrolmen opened fire on unarmed SC State students protesting for the integration of a bowling alley that refused to comply with federal law. Three killed, 28 wounded. No law enforcement officers were questioned, arrested or charged.

A call for permanent commemoration of Albert Gray and Douglas Jones:

In 2013, the college dedicated the Association of African-American Students’ Room to Gray and Jones and it has been referred to as the Gray-Jones Room ever since. This is the only visible remembrance of the men and their courage that exists on campus today. It is located in the basement of the cafeteria and used for campus events and serves as a space for faculty to have lunch. With the upcoming renovation of Burwell, the relocation of the Gray-Jones legacy is uncertain.

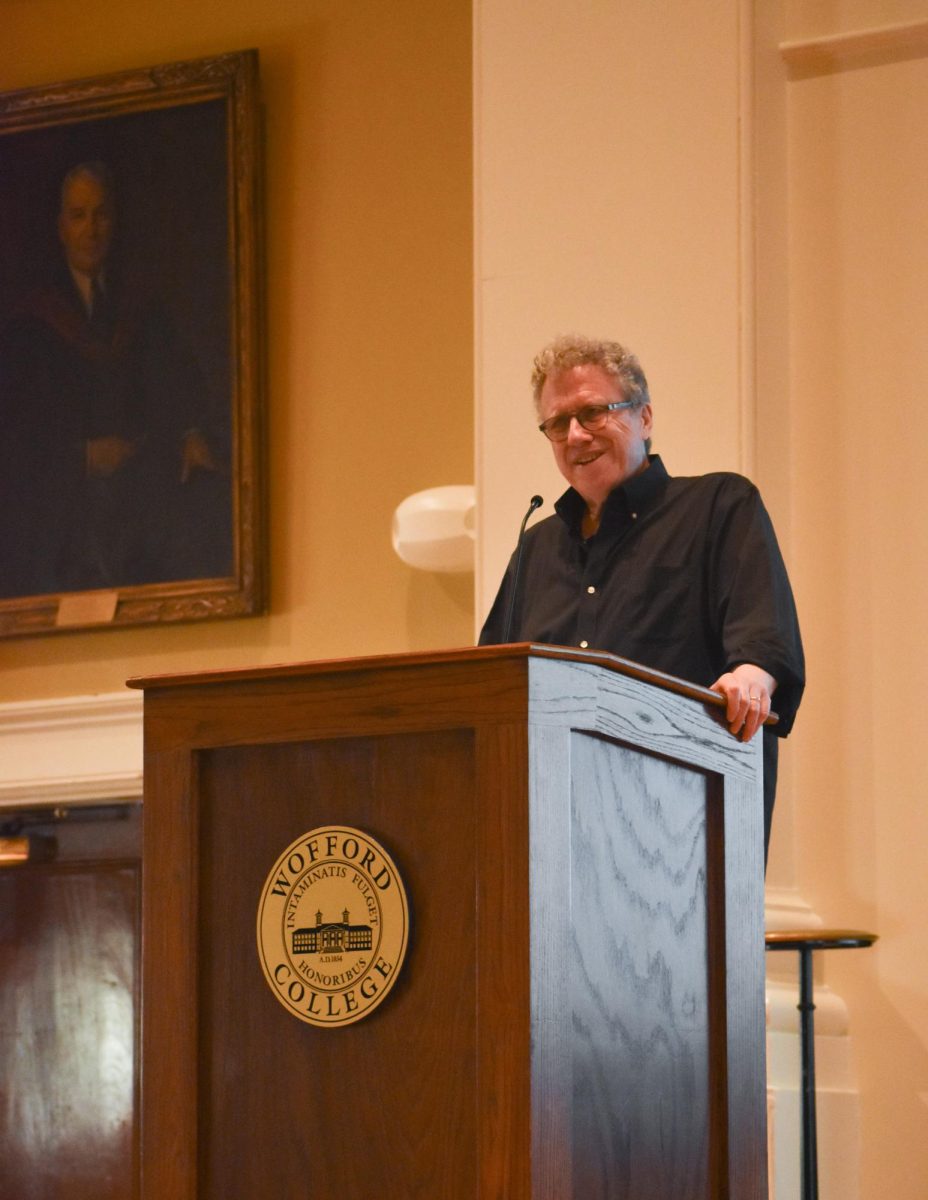

As a tour guide I am trained to talk about the various symbols and monuments around campus, but it is clear to anyone with a critical eye that the campus’s commemorative monuments are completely white washed, with the exception of the “Back of the College plaque,” “the Gray Jones Room” which few know its significance, and the “Thinking Men” etching in the wall on the ground floor of Old Main. Wofford fails to fully acknowledge and take responsibility for its troublesome past with people of color in a manner that effectively educates the students and visitors on campus.There is no time more appropriate to address and right this long-standing wrong than now.

I call on the senior class of 2021 to take on the responsibility of an institution and commission a respectful and appropriate monument to these two students that is comparable to other monuments around our campus such as the Light Statue outside of the library, Jerry Richardson statue outside of the Football center, large portraits of presidents and benefactors of the college and even entire buildings.

In collaboration with students, specifically those affiliated with Black organizations on campus, such as Wofford Women of Color, Wofford Men of Color, Omega Psi Phi, Kappa Alpha Psi, Black Student Alliance and others, the 2021 class gift should be donated to the persons of color who broke ground on a long road to diversity and inclusion at Wofford College.

Their exhibition of bravery, despite the verbal and physical opposition towards integration across the state leading up to, and persisting throughout, their time at Wofford, deserves significantly more recognition than the college affords them. The class of 2021’s ability and opportunity to preserve their work as pioneers of Black pride and allyship at Wofford should not be overlooked.