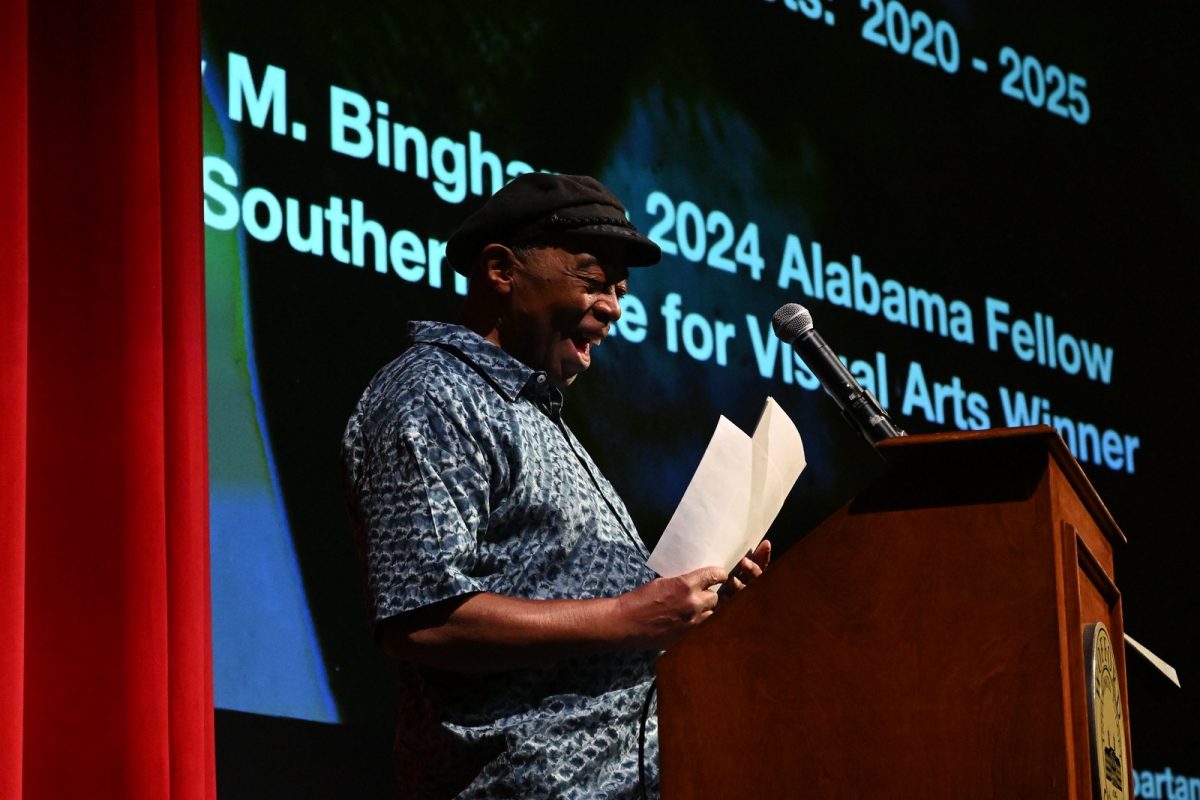

“Don’t let the idea of something being revolutionary scare you,” said Ricky L. Jones, professor of pan-African studies at the University of Louisville, during his Feb. 16 webinar on black history and critical race theory.

“Black studies is the most radical and impactful insurgency that higher education has ever seen. There is no revolutionary movement in higher ed that rivals black studies,” Jones said, quoting Molefi Asante, chair of Africology and African American studies at Temple University.

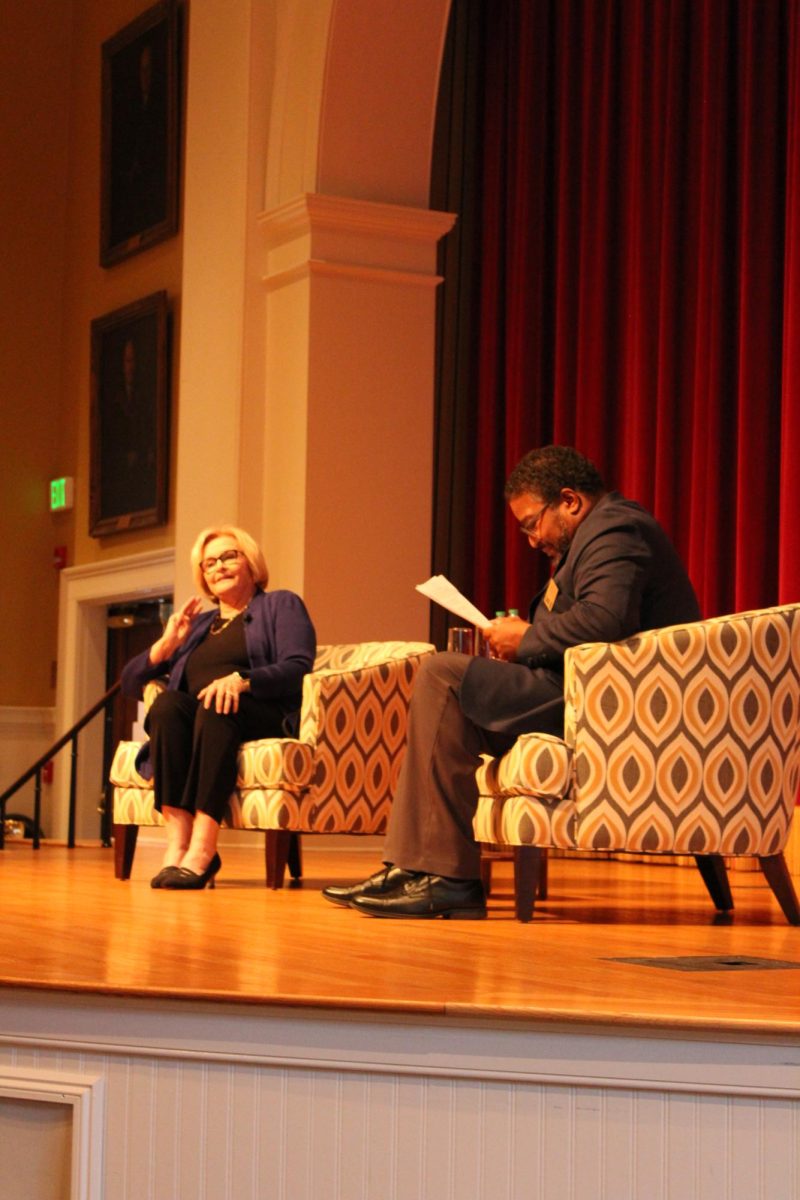

The webinar, hosted by Wofford’s Chief Equity Officer Dwain C. Pruitt, centered on discussion of the controversies surrounding black studies and critical race theory, as well as the importance of teaching black and other ethnic histories. It was one of Wofford’s many Black History Month events and was open to the public through Zoom.

“Slavery was America’s second sin,” Jones said. “America’s first sin was the mistreatment of Native people already here when folks claimed to have discovered this country.”

“What was done to our Native American brothers and sisters is reprehensible—it’s a population that has been all but extinguished in this country, and we need to recognize that, honor that and at some point do something viable about that, because the legacy of that is shameful,” Jones said.

Jones also spoke about the necessity of black studies in education and how black studies as a subject has come under fire in recent years.

“After 2020, when we heard so much across the country from companies and educational institutions (saying) ‘we see you, we hear you, we understand you, we didn’t know it was this bad,’ people have turned, and they have attacked black studies and other ethnic studies programs around the country,” Jones said.

Jones also addressed fears that he thought people may have about ethnic studies being discriminatory towards white people, a question often swirling around discussions about critical race theory in the media.

“Simply because something is called black studies, or Latin-American studies, or Asian-American studies, doesn’t make it ‘racist’ any more than having a women and gender studies department makes it sexist. That’s simply not the case,” Jones said.

Jones spoke briefly about white supremacy in education and how he believed it leaves nonwhite students with a false inferiority complex.

“White supremacy in American education is dangerous. It’s always been there, but it’s dangerous,” Jones said. “I can’t tell you how many students I’ve taught who tell me I’m the first black male teacher they’ve ever had at the college level. Some say I’m the only black teacher they’ve ever had.”

He also asserted that white supremacy in education has the reverse effect on white students, leaving them with a superiority complex, replicating a cycle.

“If some of the forces that be are successful in their anti- (Critical Race Theory) movement, it will be highly problematic for us to do better at something we haven’t been great at in the first place—that is, having legitimate educational models of discussion about race and racism.”

Jones also responded during the Q&A portion to a question about alleviating some students’ fears that supporting critical race theory may make them seem “too liberal,” or erase their conservative or Republican identity.

“I tell my students, it is not my job to force them to think like me, but it is my job to force them to think,” Jones said.

“In political philosophy, we talk about ethics,” Jones said. “The question that I ask my students is, ‘let’s explore what’s right, and what’s wrong.’ Slavery: was it right, or was it wrong? Segregation: is it right? Is it wrong?”

Jones gave a few more examples, including barring women from voting until 1920, paying women less than their male counterparts in the workplace and disproportionately policing black neighborhoods and incarcerating black people.

“My thing is, this isn’t about being Democrat or Republican,” Jones said. “Make decisions based on what is right, and what is wrong.”

“My hope would be, if a student were to leave our classes and get into the political arena, whether they choose to be a Democrat, Republican, Green Party or whatnot, they would be more driven by the ethics of the situation—what is right and what is wrong—than driven by party lines and party ideology,” Jones said.