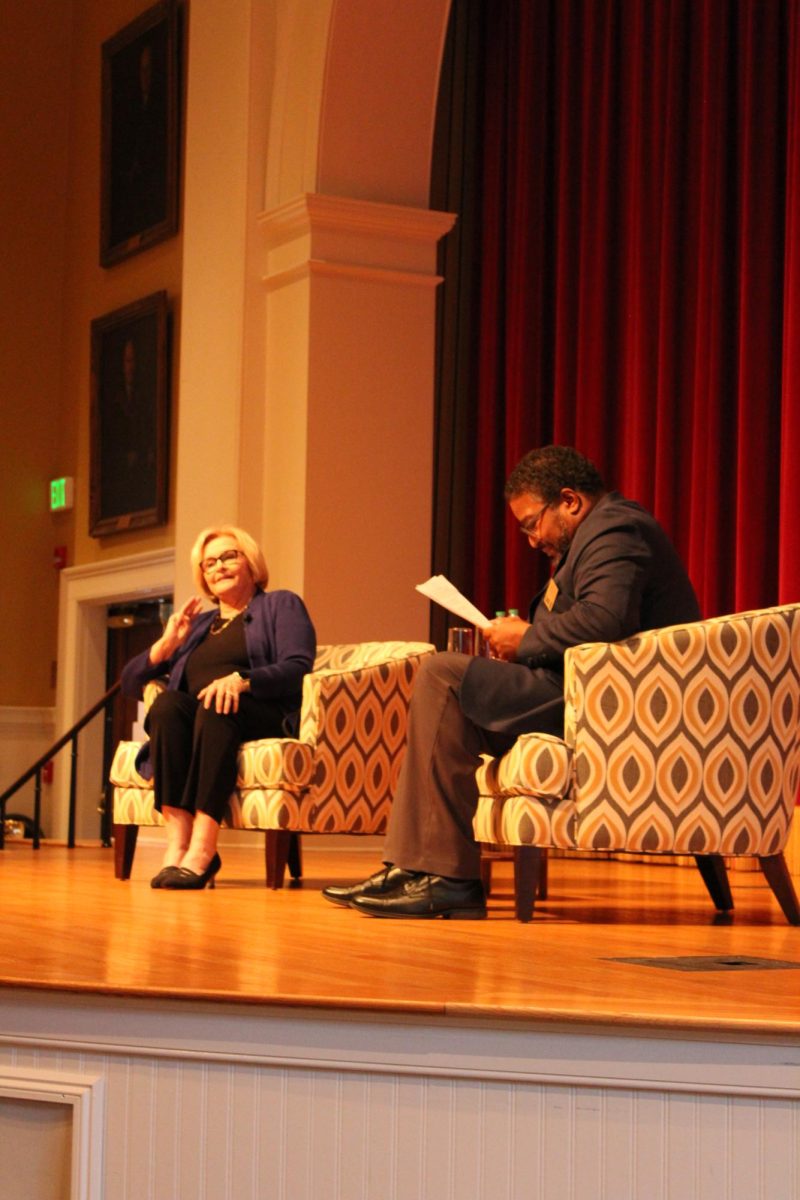

Rev. Ron Robinson and Douglas Clark, visiting assistant professor of Religion, highlighted the importance of open discussion of religion and its sometimes sordid history with social justice issues in the event titled, “Social Justice in the Christian Tradition”.

Robinson and Clark held the discussion on Feb. 9 about their relation to social justice in the Church, the ties of Christianity to social justice issues of the past and how social justice issues should be dealt with by the Church in the future.

Reflecting on their backgrounds of growing up in religious households where social justice was supported by Christian faith, both had a plethora of wisdom to share.

Clark has a unique perspective on this issue since both of Clark’s parents attended seminary.

“They raised us to believe that Christians are opposed to violence and war, Christians care about the environment, Christians care about social and economic equality and especially about racial justice,” Clark said.

Additionally, in an effort to be anti-racist, Clark and his family attended a historically black church throughout his childhood. He said that his experience of growing up in this environment gave him immense respect and appreciation for Black christianity and the Black church. Robinson also grew up in a religious household that placed an emphasis on helping others. Robinson, the Wofford Chaplain, and his family focused on helping to promote equity in their community.

Even though this was not the teaching of the influences of Clark and Robinson, people have histirically used the Bible and the Christian faith to justify slavery and other methods of hatred, intolerance and violence.

When looking at the history of the Christian church as a whole, Clark recommends that his students think of the 19th century as being “yesterday.”

In the aggregate of religious history, events occuring in the 19th century are far more recent compared to other religious historical events, like the formation of Christianity that occurred two thousand years ago.

“The idea that the church would not be involved in politics is an innovation created by white southern Protestants in the 19th century,” said Clark. This idea was completely new and did not have much justification theologically.

Despite this change occurring at the time, the two biggest slave revolts were ones led by Denmark Vesey and Nat Turner, who based their participation in leading the revolts on their Christian beliefs.

With its complicated and sometimes opposing views to social justice, it can be difficult to know what to think about Christianity’s place in the discussion.

“Sometimes students have only experienced religion as being against the things that they value,” Robinson said.

Additionally, students often criticize organized religion. However, Robinson states that organized religion has benefits when establishing social justice.

“The things we are able to do collectively are a lot bigger than the things we can do by ourselves,” Robinson said.

When examining topics such as religion, it’s important to keep an open mind. Robinson suggested not to assume that there is a singular religious view containing universal truth. Clark added that one should be sure to keep in mind the diversity of the human experience.

There are also relevant Wofford connections to the topic. Clark mentioned a man by the name of Sancho who can be found in the Wofford archives. Sancho was a Muslim in Africa who was kidnapped and enslaved and later converted to Methodism.

Sancho, despite becoming a Methodist, was still religiously persecuted.

“There is also a rich history of justice work within the Christian tradition, including in Wofford’s history and the history of South Carolina Methodism, that people need to know about and draw on,” Clark said.