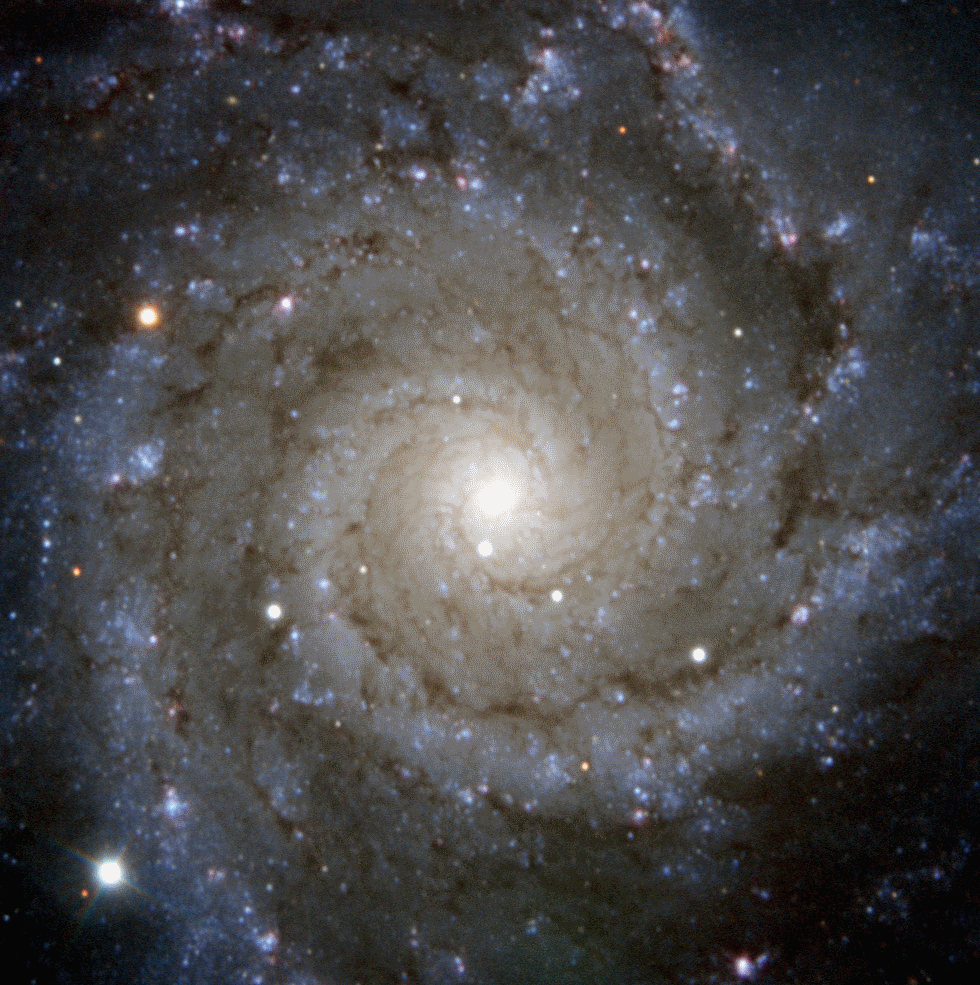

Messier 74, Boeshaar’s favorite photo captured by the Hubble. Boeshaar, now a physics professor at Wofford, worked on the Hubble telescope.

By Kayla Southwood, contributing writer

Nearly 350 miles above the surface of the Earth orbits a 27,000 pound Cassegrain reflector telescope. Better known as The Hubble, this world-class piece of technology is renowned as the most significant advancement in astronomy since Galileo’s telescope.

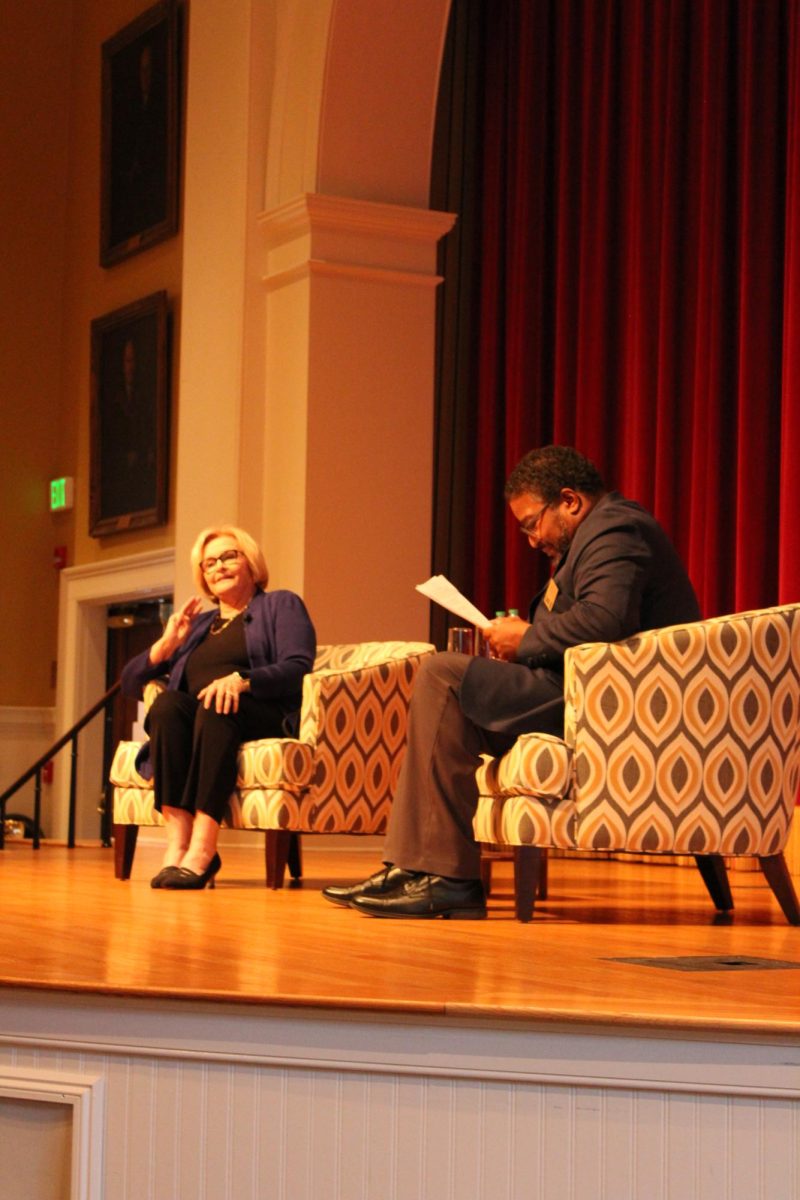

Meanwhile, in the bottom floor of the Milliken Science Center on the Wofford College campus, sits the office of the former assistant menagerie manager of the Hubble, Gregg Boeshaar, professor of physics.

Boeshaar, known by his students as “Dr. B,” was working as a teacher and researcher in Seattle in 1980 when a colleague called to ask if he’d be interested in working on a space telescope recently subcontracted for Ohio State University to build.

“(I thought) I could continue doing the research I’m doing, advancing in little bits and pieces, or I could look at the lessons of history and make a much bigger impact in astronomy by helping the next generation telescope get online, and that is going to make a big difference,” Boeshaar said.

He then packed up his office and his home and moved his life back to Ohio State, where he received his PhD

“It was one of those opportunities that comes along in life every now and then where, if you can take it, you absolutely should,” he said. “It was the most fun I’ve ever had while being paid.”

Boeshaar became responsible for overseeing a large portion of The Hubble’s development, which included overseeing the process of testing, budgeting and its general construction.

Life working for NASA was very busy, as Boeshaar was typically pushing himself out the door around 4:30 a.m., only to bring home documentation to continue analyzing after work. He also spent an unappealing, yet impressive, amount of time traveling the country to attend various Hubble meetings.

Contrary to the serious nature one might expect from a NASA veteran, Boeshaar spoke about his work with soft buoyancy in a way someone would describe a casual hobby he enjoys rather than a revolutionary piece of technology.

“I never thought of it as being tense or hard work,” Boeshaar said “I just thought it was fun.”

Just because he enjoyed his job doesn’t mean he ever overlooked the magnitude of the work.

Boeshaar explained that, by looking at the history of science, one could safely assume The Hubble’s impact would be monumental.

“Science, particularly astronomy, always advances when there’s new instrument capability,” Boeshaar said. “If you look at history around 1900, when the first large telescope came online, you’ll find that we suddenly knew immeasurably more about the universe.”

He went on to describe how Edwin Hubble, an observer of astronomy in the 1920’s, was able to realize the expansion of the universe, a ground-breaking discovery, with a mere 100-inch telescope, so Boeshaar knew The Hubble wouldn’t be something to overlook.

“We were actually able to see how stars form, proof of black holes, how galaxies interact on a large scale and what the universe was like at distances that went back 12.5 billion years for a system that had apparently started at 13 billion years,” he said. “It made buckets of difference in every possible aspect.”

As Boeshaar talked about his past days at NASA, he was reminded of how grateful he is to have taken the leap and accepted the job.

“Sometimes if you make odd choices, it pays off. Never look at your degree as the only thing you’re going to do in life,” Boeshaar said. “If I had, I’d still be teaching without ever having this experience.

“I had computer software skills, not just astronomy skills. If you have a breadth of things you can do, there are a lot of opportunities you can fit yourself into, and I was never particularly shy about taking those opportunities. Life will occasionally open its doors for you.”

Aside from Hubble’s legacy, Boeshaar also experienced other significant astronomical technologies, such as up-and-coming spacecrafts, infrastructure building in communication satellites and even the Challenger space shuttle at the time of its explosion, recalling the event as “grim for all sorts of reasons.”

One of his coworkers let him know something happened to the Challenger shuttle. Boeshaar then called his wife, asking her to turn on the TV, so he and his coworkers could gain clarity on the situation. He recalled telling her that it doesn’t matter what channel she turned on if what he had heard was the case.

According to Boeshaar, The Hubble was exceptionally close to launching at the time, and the accident put the brakes on the project for about three years. He worked with the project until 1987.

“If I, in 1960, was asked to anticipate Hubble or Webb, I wouldn’t have. There was nobody who could have anticipated what we’d be doing; technology takes us in its own turns,” Boeshaar said. “Space evolves technology, and technology is, in many ways, a survival key.”

He encourages students to not overlook the importance of NASA’s work, as they also provide infrastructure that allows communities to buy and sell food, do laundry, receive financial advice and much more.

In class, his main concern is getting his students engaged, and encouraging them to pursue their curiosities. He reminds us all to be humble, yet fearless.

“I never spent any time worrying about the future,” Boeshaar said. “That never got me anywhere.”