By: Omar K. Elmore, senior writer

Hollywood has a certain glimmer to it for the general public, a land of celebrity, wealth, excess and, of course, film. Getting to be around the industry a little further east, in Park City, UT, though, grounded the glitz and glam, revealing that the film business is just like any other.

The 2018 Sundance Film Festival featured some unique films, each with its own well-detailed, fictional world. There was Assassination Nation, a film that on the surface explored a city haunted by an anonymous hacker but that also took on gender roles and the worst-case scenario of the patriarchy. Monsters and Men offered a glimpse at three different perspectives on an instance of police brutality in such a realistic way that it could have been a documentary. Sorry to Bother You, a satire about corporate life and capitalism, was the most absurd, but the easiest to buy into.

Volunteering at the festival made me realize that the most far-fetched fictional world that we all suspend disbelief for is the one about Hollywood. Sundance offered its fair share of celebrities—Ethan Hawke and Idris Elba each directed a film that screened at the festival and several stars showed off their acting chops in indie narratives.

However, there’s something to the corporate side of the festival that shattered the image of a shiny industry of perfect-looking people. I volunteered for a theatre that, for most of the festival, exclusively held Press and Industry screenings. Sales agents, publicists and press showed up in droves to rate the new films and find their next big investment. Sure, they all spend their hours on-the-clock watching and reviewing films, but they are still simply on-the-clock like any other business.

Supply and demand drives the film business; there is a strong demand for well-reviewed films that somehow standout—the supply of those films is, obviously, limited. Sundance markets itself as an indie festival, though that label was truer about a decade ago. That said, they still tend to offer idiosyncratic films with some nuance instead of the usual Hollywood fodder.

Cinema is both a business and an art, and the films featured walked the line between the two distinctions. Great stories told by great directors with great performances lead to bigger sales. If the story is lacking, so will the industry interest. If the film panders too much to a general audience, the press could rip the film, lowering the value of the film.

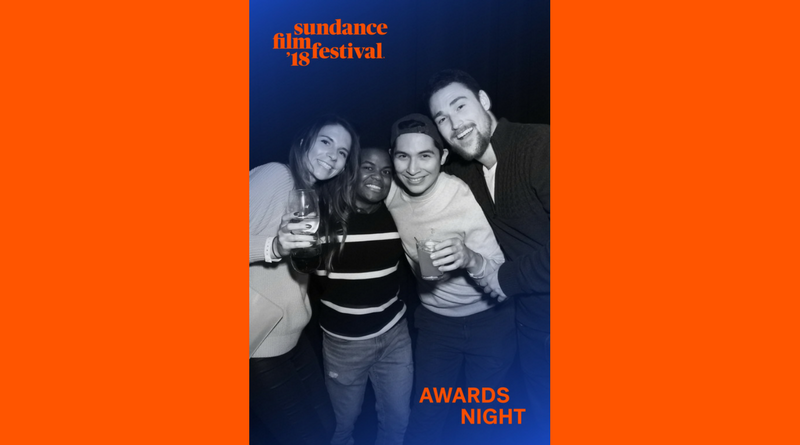

Sundance Institute takes on hundreds of volunteers to manage the 75,000 or so people that flock to Park City to participate in the biggest American film festival (Toronto International, arguably, has Sundance beat in North America). Many volunteers use the festival as a networking opportunity, meeting other creators to get some kind of an in with the industry. Others simply like the benefits of volunteering—free entry into screenings when not on shift, an invitation to the Awards Night party and an excuse to spend a week in the mountains.

Interim offered a chance for me to both network with the business and explore the art of the festival, but the biggest benefit of the opportunity was one I did not expect. The industry was demystified and, with the blinding shine of Hollywood removed, I can clearly see a path for myself to join in the industry for which I just volunteered.