The difference between silent and silenced

Orta San Giulio, a lake-side villa in northern Italy, is an unassuming and tucked-away destination about two hours by train from former-capital, Turin. The village rests on a small peninsula that extends down, out, and into Lake Orta from the foothills of the Alps. Its train station is one from the movies: the platform is about 50 feet long and one lone man stands inside the wooden shack but knows no English. It feels like a safe haven from the chaos of Italian cities.

Two young women approach the platform with a pizza box and umbrella in tote. Rain falls sleepily over the Orta San Giulio, but it’s off-season for tourism so the taxi drivers are not out. The women have walked up from the lake to the top of the hill towards the train station to catch the last train back to Turin where they will stay for the night. The whistle blows and the women, plus two other young men, wait for the conductor to welcome them aboard. The women are relieved to find the train empty with plenty of available seats.

As they are about to sit, one man asks the woman holding the box what she is holding in broken English. She does not answer, and before she has a chance, her friend whispers not to respond in English. They ignore the man, but he continues to inquire about the box, the women and if they know English.

I am the friend. I know English. But in an effort to discourage any conversation with this man who was quickly getting aggressive, I responded with a simple “no.” Thinking he outsmarted me, the man insisted “no” is an English word. I answered back that I speak Spanish, well aware that “no” is shared by both languages.

Now seated in the aisle with my friend by the window, I stare at the man and will him to disappear. Suddenly the emptiness and quietness of the train is no longer a blessing. The man’s friend says nothing but I make eye contact with him to see that he is also uncomfortable with his friend’s behavior.

The conductor walks through and orders the men, in Italian, to leave the girls alone. The man who wants to know if our box contained pizza and if he could have it has no idea I understand his attempts to get me to speak with him in English, nor the jokes he makes to his friend in Italian.

He leans over and touches my knee. My stare transforms into a glare. I look behind me, indicating that the conductor is near and will return to curtail this harassment. The man’s voice increases by an octave as he mocks my face and my refusal to engage with him in conversation. He walks away towards the other car but only briefly. Sharply turning 180 degrees, the man approaches my friend and me yelling more English, but this time, he selects a vulgar vocabulary of two words—one a verb and another a derogatory term for the female genitalia—and makes a gesture of penetration. My stare continues.

The train slows down as it approaches its first stop. The silent friend reminds the man it is their stop. They leave.

I am 20 years old and have traveled extensively now. I know English and Spanish, I’m learning Italian, I am slightly conversational in French and Portuguese, plus I could count to 20 and greet someone in Swahili if needed. I could even thank someone in Hindi, Tibetan, Russian and Arabic. I am filled with knowledge of words, but while facing the man on the train, I was mute.

There are times when choosing to be silent is a sign of maturity. We are silent to show respect in class, during presentations, during moments of tragedy. We are silent when we choose to mull on our words before we speak. We are silent when we listen to our loved ones. That evening on the train I was not silent by volition; I was silenced.

After the train left the station where the men got off, I was angry with myself for letting him silence me. In that moment, though, I trusted it was safest not to engage, to feign a lack of knowledge thus belittling my intelligence. This, after months of independent travel and a study of the artistic expression by females in the women’s rights movement, is embarrassing. I’ve spent almost a whole year abroad and still do not feel assured to stand up for myself and tell a man to stop bothering me because I fear—and I know—he could react violently to my opposition.

While I wish I could conclude my assignment as foreign correspondent to the Old Gold and Black with a letter of gushing wonder for the world I’ve come to know, I’d be remised not to take this opportunity and report back on a truth I’ve found on five continents in the past three years: this is what it is like to travel as a young woman today. The world is certainly wonderful, and before I’ll even return to the States for the summer, I’ll be working on applications for opportunities to take me abroad again after graduation. Ignorant men (and women) exist on trains everywhere. Wofford’s motto, “it’s your world,” isn’t an exaggeration. It is your world, so don’t let anyone take it—or your voice—from you.

After two semesters of reporting from South America and Europe, this terrier is officially signing off.

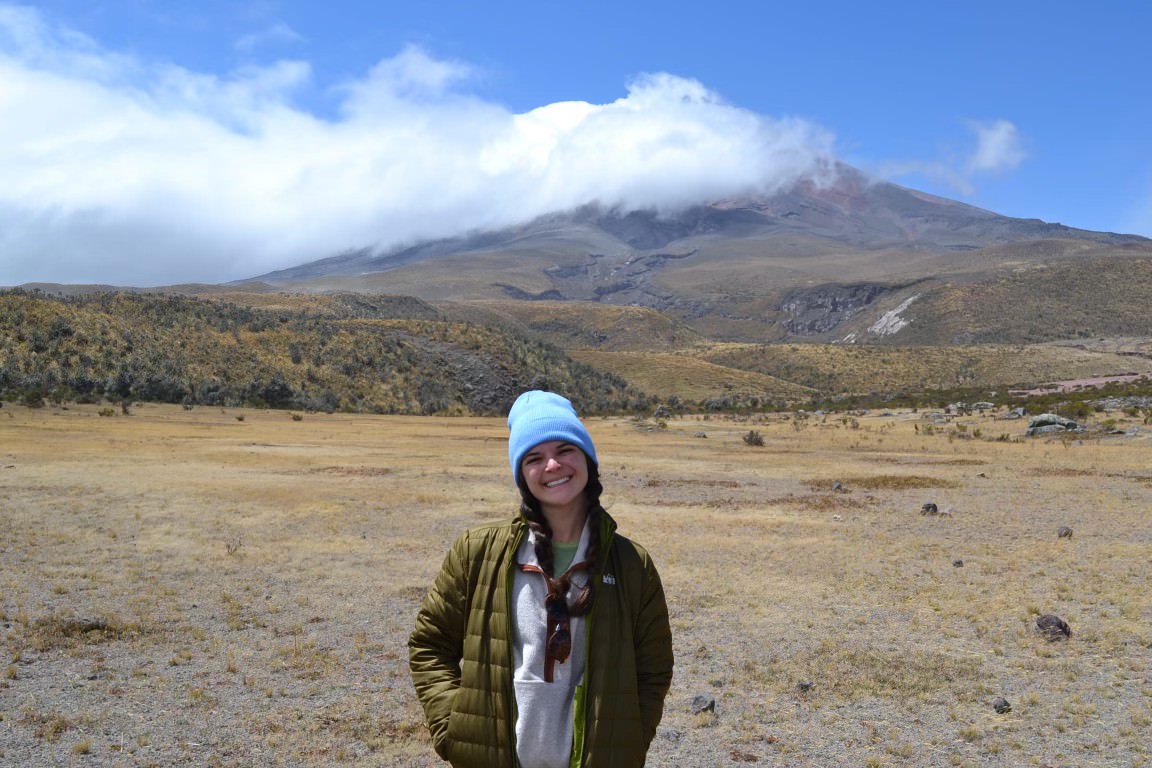

Photo Caption: In the center of Lake Orta, there is a small island with a few homes and a single restaurant. The boats can be rented to access the island, but there are plenty of restaurants along the water. Orta San Giulio is at most an hour drive to Switzerland in the north.