Responding and reacting to peculiar questions

Studying abroad, at its surface level, is about immersion. A successful semester in another country can take many forms, but it often includes trying new foods, respecting the customs, learning, bettering or expanding a language and seeing new places. A full semester allows a student to go beyond “taste testing;” new words, new dishes and new sights become a daily diet. I eat Chilean expressions for breakfast, visit another museum for lunch, snack on a sopaipilla(a fried disc of pumpkin dough) as I take the micro, or Chilean bus, to the local theater for a viewing of an indie-film about a Haitian immigrant in Santiago for my dinner. I never go hungry here; there is always something to learn.

For instance, I’ve learned there exists a cross-continental question people wonder about Americans: “Do you like Obama?” As an American abroad for the third time as a Wofford student, I have noticed this in Tanzania, Nepal and now Chile. The question manifests itself in a variety of forms:

“Are you team Obama?”

“Trump? Obama?”

“Did you like President Obama even though he’s black?”

Before I address the inherent problems with the third form, I find it unbelievable to realize that Barack Obama was elected 10 years ago. That is half of my life; I was barely 10 years old the night my parents permitted me to stay up past my curfew to watch the 2008 election results. Although Former-President Obama officially left the Oval Office under two years ago, it feels as though several presidential terms have passed—perhaps an effect of following more current events with greater context than I was intellectually capable of during Obama’s first term, or perhaps the result of traveling abroad three times during President Trump’s term and feeling very aware of America’s perception by foreigners. I still find it funny that 10 years after his initial election, Obama is still the object of foreign intrigue.

The third version of the question arose during my time on the northern Chilean coast, when my friends and I were graciously invited to dinner with our beach neighbors. The father of the family told us about his lifestyle working with a mining company as he grilled. He shared plenty of valuable insight about his nation and his identity as a Chilean (alluding to but purposefully ignoring any facts from the period of the Chilean dictatorship). The conversation was reciprocal; we, too, shared experiences as Americans and compared the major social issues in Chile and the States, such as police violence, women’s rights and immigration.

In many times and places, I have been described the current situation on immigration in Chile. In my course on contemporary Latin American poetry, we have studied the African influences on Brazilian and Caribbean poetry from the late 19thcentury. In the courses like this one designed for international students, the professors are encouraged to integrate their curriculum with Chilean context to enhance the foreign students’ understanding of the country. Thus, my poetry professor has mentioned numerous times as we read Afro-Cuban poems, for example, that he never “saw a black person in my life until I was 18, except in the movies”. In my homestay, we often keep the news (or a Chilean gameshow) on the television in the background. When the headlines pertain to socio-political issues in Columbia and Venezuela, it is more likely than not that one of my family members will make a remark about the presence of immigrants in Chile. Even though they have explained to me their opinions on Colombians and Venezuelans before, they once more insist that the immigrants are lazy and lawless. Usually they conclude with a comment like, “you know how it is, Americans have the same problem.” We do?

I do not mean to generalize all of Chile’s views on immigration or race. It is key to remember that not every Chilean explains (or complains about) immigration in the same manner. For example, my Spanish course is taught by a professor who explicitly reveals his support of immigrants in Chile and encourages the diversity it has created. He recognizes, as many of my peer exchange students have noticed as well, that Chile is geographically isolated in all directions by either mountains or ocean. Historically, Chile has long been an overwhelmingly homogenous society. As an American, from a nation literally created by immigrants, this is important to take into account when considering how some Chileans defend the impact of immigration on their country.

So when the middle-aged Chilean man asked my six friends and I if we like Obama, even though he is black, I wasn’t that surprised. His question was immensely racist—from an American perspective. For a Chilean, I can’t say for certain how improper his “qualifying factor” for judging Obama’s presidency would seem. This has been one of the most-challenging dynamics of being an American abroad: how do I recognize my American bias in interacting with others, and how can I better understand what aspect of American society is influencing whichever generalization? Do I accept that generalization because it is half-true, or do I attempt to counter that generalization because it is half-false?

The only word I have for questions and remarks like these is “peculiar.” I can’t call them offensive, because if anyone should feel offended, it’s Obama. His efficacy as the leader of the United States is doubted for a matter of his skin color, and it’s 2018, not 1958. Admittedly, during my first time abroad in Tanzania, I was especially perplexed by the image and generalizations other nations have perceived of America. That’s really all that stands out about America? This is what, as an American, you assume of me?I realized quickly that I had no idea “how to be an American abroad.” Am I supposed to act diplomatically, avoiding any answer with own ideologies but instead taking an opportunity to provide a glimpse of America from outside the frame of a news camera? Why do I feel defensive when my liberal Chilean professor (whom I admire greatly) openly critiques our access to arms in the States? Why do I not know how to explain that not all Americans are racist? It’d be awfully naïve—imperialistic even—to expect a red carpet and showers of praise while abroad just for being an American. I just did not imagine how difficult it would seem to represent so large and so complex a nation while traveling in equally complex corners of the world. It is humbling to say the least to bear the weight of America’s honor and dishonor as I travel.

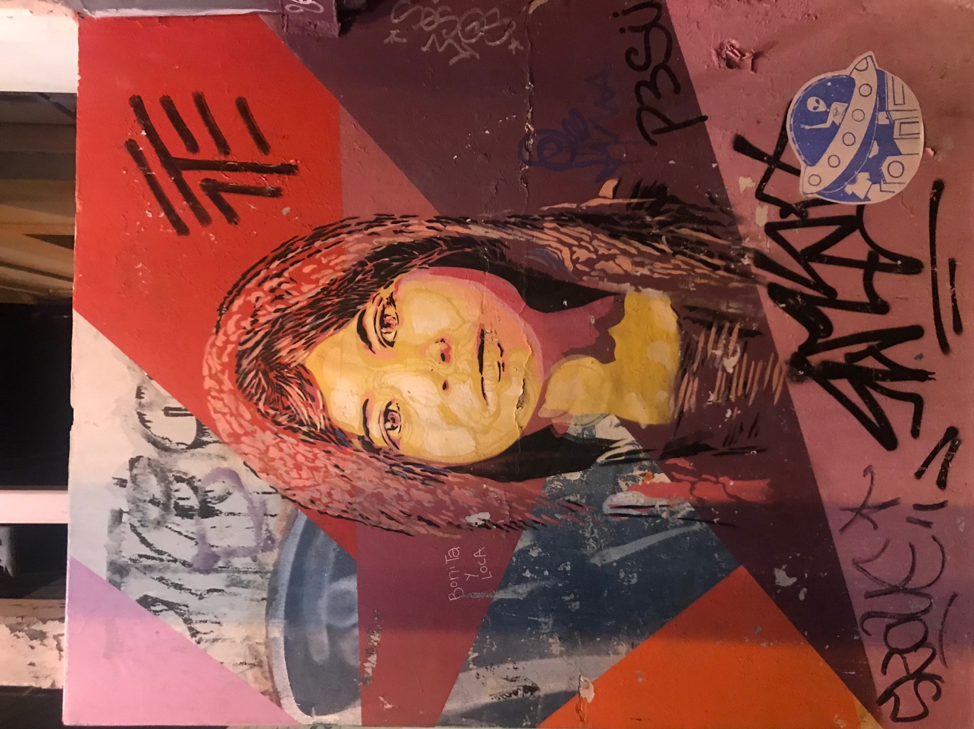

Photo Caption: This mural in one of Valparaiso’s many cerros, or neighborhoods nestled into the hillside, is by a known Venezuelan street artist who began painting faces of fellow Venezuelans leaving their country in search of better lives.